What does your backup do, Sam?

What does your backup do, Sam?

We have been working on our postgres backup routines lately and spent a lot of time convincing ourselves that we have a working setup. This actually took a considerable amount of time, because we had a lot of skepticism after our recent firedrills. We think that skepticism is probably the healthy approach to backup routines anyway. Most people know that backups are important, but putting a lot of work into it has given us reasons to think about what problems that backups solve.

We already mentioned in a previous blogpost that we have a replication server set up, and hopefully the chance that both the master and the standby go down are pretty low. So in a normal outage, we hope to be able to restore services by promoting the standby to master instead of doing a full recovery from backup, which will take longer. But there are scenarios where our standby won’t save us. The recent heartbreaking gitlab database incident is a good example. Replication had stopped in this instance and the activity was actually to get it up and running again.

Another scenario would be when your standby and master are both in the same data center. In this case, maybe a network outage would make both inaccessible and give you a complete loss of service. At this point, if you had backups, you could create new database servers. Obviously, that requires your backup to also be available off-site.

But there are more subtle type of problems where a standby can not help you. One example would be when a developer introduces a bug in an application that causes it to overwrite valid data with nonsense. In this case, the standby is just going to happily write the changes that the master does and only a backup or a log file could help you recover the lost data. Another example might be a script or person executing a database query that drops a table on the wrong server or in the wrong environment.

We’ve been thinking a little about how we could handle such outages and have some ideas of our ability to handle them, but we haven’t tested ourselves yet. An exercise that we want to do, is to delete a table from a database in QA and attempt to recover that data without losing any transactions after the table is dropped.

For example:

- Everything’s working fine

- Developer makes mistake, dropping a table

- Developer goes to lunch

- Users keep creating traffic and transactions

- Developer comes back from lunch, notices problem

- ???

- Developer goes home after work

We think we could manage to sort out the above incident. Our current idea is that we would use our backup and our WAL archive to do a point in time recovery to time 1. We wouldn’t do that on our current master database, because would cause us to lose the transactions between time 1 and time 5. So we’d set up an entirely new database server from the backup instead. From this new instance, we can do a full dump of any relevant tables using pg_dump. Hopefully, we can then import the generated SQL to our master database.

This is a problem you can’t really solve with a standby.

In our setup, a backup job runs pg_backup in the middle of the night. Our master server has an archive_command that it uses to store WAL segments. Both the basebackups and the wal archive are stored on and off-site, so we’ll have access even if the network in our data centers are down for some reason. We have also configured wal_keep_segments, because our backup-tests revealed that a database set up from backup was not able to start streaming replication without it. We don’t fully understand this, as all the required WAL segments are present in archive.

The first step of what a developer could be doing at time 5, would be to set up a new postgres server. They can do that by fetching the latest basebackup from either on-site or off-site, and extract it on a server. The next step would be to create a recovery.conf, setting it up with the correct restore_command to extract WAL segments from the archive, and set the recovery_target_time right before time 2.

Starting this postgres instance should then produce a database server with the same state as what was in the master at time 2. Depending on the amount of WAL segments in the archive, this could take a while.

When it’s done, the developer could use pg_dump, providing the correct --table argument and database names, which should produce a .sql file containing INSERT statements for the missing data.

They can then replay the remaining WAL by setting a later recovery_target_time and restarting the fresh database instance, which should provide them with a database server where the table has been dropped. They can use the fresh database instance to test that importing their dump fixes the problem, or at least doesn’t make it worse. After they’ve tested it and verified that it works, they can do the import on the master server and go home after work. Or that’s the idea.

A recovery is probably harder if the table has been truncated or updated wrongly, which might mean someone has to set up some sort of data reconciliation. But it might still be possible.

Being confident in our backups

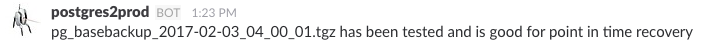

One of the things we’ve done in order to be confident in our ability to restore from backup, is to set up an automated job that creates a database instance from backup every day. This database will then connect as a standby to our current master and verify that it can start streaming replication. We throw away this database after it’s been verified that the backup is good. It’s a really nice feeling when the backup-test script posts on slack that it has successfully done a point-in-time-recovery of a backup:

Making this backup-test script was a pretty simple job. It also serves as living documentation of how to do a recovery procedure. And since it’s being run every day, we can be confident that the recovery procedure actually works, unlike some 3-year old recovery procedure documentation on a wiki. A nice side-effect of this is that we actually know how long it would take us to recover from backup.

We haven’t yet completed an automated test for our off-site backup. In principle, it should work exactly the same way, but the wal archive is a different source so the recovery procedure is actually slightly different. We need to do an exercise to determine if we need to write some tooling around this recovery procedure to feel confident about it.

We do want to run firedrills on recovery situations. The table-drop scenario recovery is an example of a recovery job that is more complicated than the test that we run every day, so it would be good to do it manually a few times to verify that we can recover the data in such situations. And it could help us find the limits of what we are actually able to do. Maybe we can do more than we think.